How Slow is "Slow" When it Comes to Psychiatric Drug Tapering?

CAUTION: Most of the information in this Review is anecdotal knowledge that has been collected and reported by laypeople and is being shared for educational purposes; it is not and should not be taken to be medical advice, nor should it be taken as advice or encouragement that you or anyone should come off medications. It can be very risky to reduce or stop any psychiatric drug, and it can be especially dangerous and potentially life-threatening when done rapidly. Any reductions to psychiatric drug dosages should involve careful preparation and are best made in collaboration with a prescriber who is well-informed about a wide range of risk-minimizing approaches to psychiatric drug tapering.

Introduction

This Review walks through what the layperson withdrawal community considers to be “slow” when it comes to tapering off psychiatric drugs, and explores the risks associated with tapering off too quickly. Our intention in putting together this information is not to “tell you what you should do” or to frighten you. Rather, it’s to offer the valuable insights and wisdom of the layperson withdrawal community that so often never make it to the light of day.

At this time, there is no way to know exactly how many or exactly what percentage of people face serious and prolonged difficulties from coming off psychiatric drugs too quickly, because so little is known or understood about withdrawal more generally. We don’t have any reliable statistics. There have been no large studies of any kind on this phenomenon, and most of the sizable studies use participants who may not represent most users. All we really have are our experiences, our stories, and the collective knowledge growing among us in our communities. It’s this that we’re sharing with you in this Review.

Are you yearning to come off psychiatric drugs as soon as possible? Please read this first.

We at ICI know from first-hand experience how strong the desire to withdraw quickly from psychiatric medications can be. Indeed, once that light turns on and the realization sinks in that a future “off meds” is calling, it can feel brutally painful to keep swallowing pill after pill, day after day, month after month. If you are in that place right now — yearning to “just be free”, to just “get it over with”, for whatever personal (and very valid!) reasons you may have — boy, do we feel you.

We have been there, ourselves. Know that you are far from alone. But in the midst of that desire, we hope you’ll nonetheless stick around and read this Review of the most risk-minimizing tapering rates in its entirety before deciding on a rapid taper — not because we have any intention of suppressing that yearning you feel for your future, but in fact for the very opposite reason: If you decide for yourself that reducing or coming off psychiatric drugs is right for you, we are rooting for you to have the smoothest taper possible so that you have a better chance of not just successfully tapering off them, but staying off them, as well.

This Review has been written entirely from a place of deep respect for, solidarity with, and commitment to anyone considering withdrawing from psychiatric drugs. We believe in you and your potential to live a life that’s fully in line with what feels right for you — whether that means staying on, reducing some, or coming off all psychiatric drugs. But we are acutely aware, as well, of the darkness encompassing so much of the public understanding regarding the impacts of psychiatric drugs on the brain and body, and how this shapes the experiences we have coming off them. And we feel compelled to shine a light on this darkness, because far too many of our friends and fellows — and many of us at ICI as well — have been harmed because of it.

This is why we’ve written this Review of what we have learned about the rates for tapering off psychiatric drugs that seem to yield the smoothest outcomes in the layperson withdrawal community. We hope you’ll hang in there with us to its end, so that by the time you settle on the speed of your taper — whether it’s slow, fast, or somewhere in between — the choice you make will be meaningful and fully informed.

How slow is “slow” when it comes to tapering off psychiatric drugs?

It’s not uncommon to hear about how important it is to come off psychiatric drugs “slowly”, and to not stop psychiatric drugs “abruptly”. But what do these words really mean? Is “slow” a few weeks of tapering? A few months? A few years?

Many people are usually left either to guess the answers to these questions for themselves or to simply accept whatever they’ve read online at mental health websites or been told by their prescribers. As a result, they may feel confident that they are coming off “slowly” when they actually may not be. Then, if they start to encounter emotional, mental, or physical problems, they or others around them may misinterpret what’s occurring as an “underlying mental illness re-emerging” or a “relapse”. They may then be told, or believe that they’ve learned on their own, the following lesson: “You tried coming off your psychiatric medications slowly and it didn’t work. You must be one of those people who needs medications indefinitely in order to manage your life.”

This is a message that can lead to deep despair and hopelessness. And it’s also a message that completely ignores the very real impacts that psychiatric drugs have on the body, and the substantial problems that withdrawing from them too rapidly can cause.

What do most prescribers and researchers say “slow” means?

The definition of “slow” that people typically hear in many doctors’ and psychiatrists' offices, clinics, hospitals, detox facilities, and across the medical literature is typically defined anywhere from a few days or weeks to a few months. Meanwhile, people have reported that more “withdrawal-friendly” practitioners and facilities — in other words, those who recognize the reality of psychiatric drug withdrawal and are open and willing to help people come off — suggest rates that are closer to 6 to 18 months of tapering, and even longer, depending on how many medications a person is on.

Based on our gathered anecdotal wisdom base, the layperson withdrawal community finds weeks, months, or even a year and a half to be far too fast for far too many people — especially, but not only, if they've been taking psychiatric drugs for a long time.

So exactly how slow is a “slow” psychiatric drug taper rate according to the layperson withdrawal community?

People in the layperson withdrawal community have come off psychiatric drugs at vastly different speeds with vastly different outcomes. While outcomes are often unpredictable and seemingly illogical, the differences are undoubtedly due in part to the fact that people are often in very different situations when they begin tapering: Some may have been taking only one drug for just a few months, while others may have been taking several drugs for two decades; some may be in general excellent health, and others not; some may have bodies that metabolize drugs more effectively than others’ bodies; some already be suffering uncomfortable side effects and so reducing a dose provides a noticeable alleviation of symptoms, while others may be feeling comfortable until withdrawal effects begin. Despite all these variables and differing circumstances, what the growing collective anecdotal knowledge base of our many differing experiences is showing is that, generally speaking, it seems that...

...most people most of the time have the least-disruptive, least-disabling, and most successful outcomes by reducing their psychiatric drugs at a rate between 5-10% per month, recalculated each month based on the most recent, previous month’s dose.

Is tapering at 5-10% per month of the original dose really so different from tapering at 5-10% per month of each previous month’s dose?

Yes. Making a monthly reduction of 5-10% per month, calculated upon each previous month’s dose, is very different from making a monthly reduction of 5-10% per month calculated upon the original dose that a person was taking at the start of their taper. This difference is essential to understand as it can dramatically change the speed and nature of a taper.

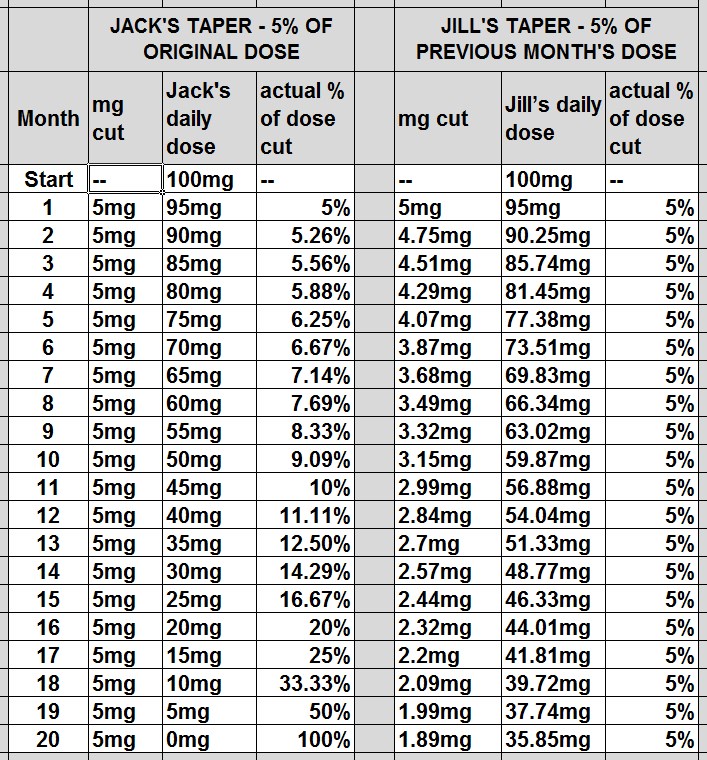

Let’s consider an example — see the comparison chart below.

If Jack is taking 100mg of drug and tapers at 5% per month, calculated based on his original starting dose of 100mg, he will be taking 95mg after 1 month, 90mg after 2 months, 85mg after 3 months and so on, until he is taking 0mg after 20 months. Conversely, if Jill cuts 5% per month, but recalculates the amount of her cut each month based on each previous month’s dose, after 1 month she’ll be taking 95mg, after 2 months 90.25mg, after 3 months 85.74mg, etc.

At first the differences between Jack and Jill’s dose cuts are not very large, but these differences increase over time. By month 15, Jack is taking 25mg, while Jill is taking 46.33mg. Two things are happening here simultaneously: The percentage size of Jack’s cuts is actually accelerating dramatically. In month 18, for example, when he goes from a 15mg dose to 10mg, even though he’s still only cutting 5% of his original, starting dose, he has actually reduced his dose by 33.33% from month 17 – that’s considered a massive cut to make in one month by the layperson withdrawal community! Meanwhile, even though Jill is still cutting 5% of her previous month’s dose, her cuts are actually decelerating in size. In month 18, when she goes from a 41.81mg dose to a 39.72mg dose, that’s a 5% cut, but she’s only cutting about 2mg or approximately 2% of her original, starting dose.

So while Jill’s approach lengthens the amount of time spent tapering, especially during the mid-to-late stages of withdrawing, many experienced laypeople report that this smoother, decelerating pace seems to be a vitally helpful approach for more responsible tapering. This may be in part because it’s common for a taper to become more difficult in its later stages. Of course, in order to prevent a taper of this kind from continuing indefinitely, at some point in the mid-to-later stages it does become necessary to slightly increase the taper rate again and make some larger dosage ‘drops’ to get fully off a drug, but by that point dosage sizes are becoming so small that even these drops are relatively tiny.

Why is a slow taper typically considered the least risky taper by laypeople?

Occasionally, there are times in which a medical emergency or serious adverse reaction necessitates rapidly stopping a drug. (If you are in such a situation, immediately consulting with a well-informed prescriber and taking careful measures to plan for the possible eventualities of rapid psychiatric drug withdrawal by working through Part 1 of ICI’s Companion Guide is wise.) Apart from those kinds of circumstances, though, reports from the layperson withdrawal community suggest that a rate of between 5-10% per month of one's current dose is the maximum taper speed at which especially problematic withdrawal symptoms can be kept at bay. This is because this slow speed seems to reduce the possible risks of extensive disruption, disability, and injury to the central nervous system (CNS).

Significant changes can begin to happen to the functioning and structure of the CNS after taking a psychiatric drug for even just a few weeks (for more on this, read ICI’s "Primer on Psychiatric Drug Tolerance, Dependence, and Withdrawal"). Because of these changes, as you withdraw, your CNS needs time to slowly re-adjust to the absence of the drug it had previously grown acclimated to. Withdrawing at a rate faster than your central nervous system can handle or adjust comfortably to can lead to its destabilization, and a subsequent cascade of mental, cognitive, emotional, sleep, and physical problems that can be anywhere on a spectrum of mild and short-lived to utterly debilitating, disabling, and long-lasting (i.e. reports range from many months to even years). Therefore, to minimize this risk, laypeople suggest to one another to follow this slow taper rate (or slower) while monitoring carefully and continually what’s happening in the body and brain.

Why the specific range of 5-10% per month and not, say, 10-15%, or 20-25%?

The range of 5-10% per month of current dose was arrived at by gathering the lay withdrawal community’s ever-growing number of anecdotal reports on outcomes from various tapering rates, and determining which range, on the whole, seems to allow for the least amount of harm. Basically, it is the considered, collective opinion of a lot of experienced people who have been communicating and examining this question with each other online and off-line for many years. For reasons not yet clear, this particular range of 5-10% seems to be the “fastest” window in which most people most of the time can taper off medications without having to go through life-disrupting emotional, mental, physical, cognitive, and sleep problems. This doesn’t mean that no withdrawal symptoms will occur in this range for all people; however, many report that when tapering in this range, most symptoms that do emerge often feel manageable, and seem to resolve relatively quickly, allowing for them to continue to participate fully in their lives as they taper down.

But I know people who’ve come off faster than 5-10% per month and had no troubles. Shouldn’t I be able to as well?

It is certainly true that some people can and do come off psychiatric drugs successfully at a faster rate than 5-10% per month—some have even successfully come off by “cold-turkeying” their drugs. Sometimes, this success with rapid or cold turkey withdrawal is reported to be easy and problem-free; other times, people report it being very difficult, but manageable enough that life can continue on largely as it was before.

However, at this time there is no way to know in advance of starting a taper how one’s central nervous system will respond to rapidly or abruptly coming off, what might happen to one’s quality of life, and how long withdrawal effects might last. Consequently, choosing to taper quickly is extremely risky. There’s a chance that any particular person will be able to handle the abrupt change with no or minimal problems, but there’s also a chance—and as many in the lay withdrawal community believe, a larger chance—that doing so will disrupt that person’s life. In fact, many people have reported that too-rapid withdrawal affected them in such a way that they became limited or outright unable to function or participate in day-to-day responsibilities, tasks, and activities for weeks, months, or even years. And once they were destabilized in this way, many have reported that going back on their medications—especially if it had been longer than a month since they’d stopped taking them—did not relieve the withdrawal symptoms. For some people, it seems that going back on their medications after an abrupt withdrawal can actually make problems worse, as can trying entirely new medications.

This is what ICI calls the “speed paradox” of psychiatric drug tapering. It's a bit like the proverbial story of the race between the tortoise and the hare: Many who taper slowly are on their medications longer over the short term, but they often feel healed and fully back to life sooner than those who quickly taper and end up facing months or years of disabling psychiatric drug withdrawal symptoms.

There are also no known supplements, herbs, tinctures, electrical or magnetic interventions or other treatments of any kind that will reliably speed up psychiatric drug withdrawal or make symptoms go away. Once the central nervous system has been destabilized by a rapid taper, all that a person really has to rely on is the body’s own innate healing capacities and time. And how much time? There is simply no way to know.

How bad can withdrawal symptoms from tapering off psychiatric drugs too quickly be?

Across online withdrawal forums and groups, it's possible to find countless reports of people’s experiences enduring rapid and cold-turkey psychiatric drug tapers. Some of the more common reports include:

- The body can become highly sensitized to the environment, foods, products, and chemicals, causing “allergic” reactions to many things that never previously caused a person problems. This can make day-to-day living especially complicated, as diets have to be drastically changed, exposure to products completely limited, etc.

- The body can become weakened or hyper-sensitized in such a way that physical activity becomes difficult if not impossible. People who’ve been active athletes and exercisers become mostly immobilized, sometimes for months or years at a time, because their bodies can no longer handle the strain.

- In other cases, people are not able to get up a flight of stairs without having a panic attack because they report that their body’s “fight or flight” response has become so impaired that it interprets any physical exertion as a life-threatening stressor. Others have reported not being able to sit up or stand for more than a minute at a time because of pervasive vertigo.

- Completely new or drastically intensified emotional and mental difficulties can emerge that reportedly make the initial problems that led people to take psychiatric drugs in the first place seem like a “walk in the park”. Some of the most common experiences include debilitating anxiety and panic, deep and unrelenting despair, panic attacks, anger and rage, obsessive and compulsive thoughts, and paranoia.

- Some people become so impaired (whether physically, mentally, or emotionally) that they lose the ability to take care of themselves or their family, work, run errands, drive a car, manage household responsibilities, cook, exercise, read or, in some situations, even leave the house. Some have had to go on short or long-term disability for the first time in their lives.

- It's not uncommon to lose the ability to sleep for more than a couple of hours at a time. Some report having these sleep difficulties for many months straight.

- Nerve disruptions of different kinds are commonly reported, including everything from irritating tingling sensations to hands and feet feeling like they are on fire all the time.

- Some people begin to have suicidal or homicidal thoughts or feelings—often for the first time in their lives. Often, people describe experiencing akathisia (which you can learn more about here) so unbearable that suicide feels like the only way out.

Despite all of this, some of us at ICI have ourselves tapered off far too rapidly, or were even ripped off "cold turkey” by poorly informed practitioners, because we didn’t have this kind of information at our disposal when we began to withdraw and didn’t know how to advocate more effectively for ourselves. We’ve been lucky enough to make it through our darkest hours and eventually heal and reclaim ourselves. But tragically, during rapid withdrawal, far too many of our friends have actually taken their own lives. It is to them, with love and respect, that we dedicate our Companion Guide—and with the hope that it doesn't have to happen to anyone else.

CAUTION: Most of the information in this Review is anecdotal knowledge that has been collected and reported by laypeople and is being shared for educational purposes; it is not and should not be taken to be medical advice, nor should it be taken as advice or encouragement that you or anyone should come off medications. It can be very risky to reduce or stop any psychiatric drug, and it can be especially dangerous and potentially life-threatening when done rapidly. Any reductions to psychiatric drug dosages should involve careful preparation and are best made in collaboration with a prescriber who is well-informed about a wide range of risk-minimizing approaches to psychiatric drug tapering.